from JetHead's Blog

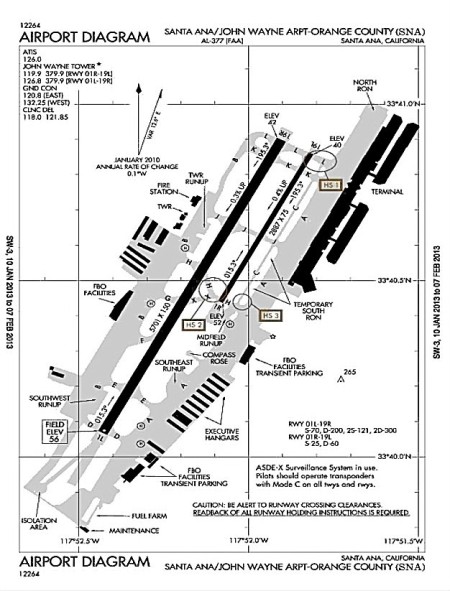

And that’s what it looks like, landing a jet on a short field which, for a transport category jet, John Wayne-Orange County (SNA) certainly is. But the video tells nothing about how it’s done, much less how it’s possible.

Besides, landing is the easy part–taking off, unless you plan to spend the rest of your life there, is the complex and more difficult maneuver. So here comes a discussion of the long and short of it.

First, consider landing–which isn’t really the more difficult challenge. Rather, stopping sixty tons of metal, fuel, flesh and bone in the allotted distance is, and taking off is more tricky than landing. Why? That’s a question of physics more than anything. Here’s a relic from the olden days:

The wily flight engineer had to enter the graph with the jet’s landing weight, speed, the airfield pressure altitude and compute the millions of foot-pounds of brake energy that much be dissipated after touchdown. See why? It’s all about choices: on landing, you have a choice that you don’t have on take-off, which is, don’t stop.

On landing, you’re in flight and can continue–go around, divert, find a longer runway; set up for a different approach. On take-off, you don’t have the option of continuing a flight you have yet to achieve, and you’ll be likely to be much heavier on take-off (fuel, which gets burned off enroute, right?) than on landing, minus one key option–staying in the air.

You have to stop. And on many runways, you have little space in which to do that.

So you’ve seen the primary challenges: weight, speed, and distance. Now for the wild cards, which are tailwinds and runway surface conditions. If you are at your threshold speed, say 150 KIAS (Knots Indicated Airspeed), but the wind is directly on your tail at 5 to 10 knots, your tires will hit the runway at 155 to 160, and the brakes will have to absorb the kinetic energy associated with that, not the 150 threshold speed.

The Byzantine brake energy chart above assumes a standard coefficient of friction, but if the runway is wet or worse, the coefficient of friction will be reduced as will brake effectiveness.

And now let’s throw in the hardware curveballs: what if one or both reversers fail to deploy? Or if an engine fails, that reverse thrust is lost as well. And if the wing spoilers fail to deploy, or the antiskid fails, or any tire blows, reducing your braking capacity by 25% per tire.

These are all contingencies that must be dealt with, and on take-off roll on a short runway, they come at you fast because you’re using a higher power setting to lift more weight of the short runway: faster acceleration means less reaction time before you’re committed to flight because stopping in the runway remaining isn’t possible.

Plus, lest you think the remedy is a longer runway, don’t forget the “Pressure Altitude” factor in the DC-8 Flight Engineer’s hands above:

Mexico City has a 12,000 foot long runway–more than twice the length of the SNA runway–but at 7,500 feet on a good day; if the temp hits 90, as it often does, MEX becomes an engineering nightmare for stopping and for taking off. Ditto Denver International. And (told you it was more complicated) if you’re not taking off but rather trying to abort on the runway, with any of the variables, wild cards and curveballs above, you’ve got a real mess on your hands.

So how is it done? It all goes back to being a junior high school boy, when the primary question in life was this: how much can I get away with?

So the first thing to do upon level-off, after we’re at cruise altitude and can finally get a decent estimate of our enroute fuel burn and thus arrival fuel weight, is haul out this chart:

Calculate the predicted landing weight–takeoff weight minus enroute fuel burn–then determine the “Landing Distance” we’ll require. The bottom three lines include the degrade factors for tailwind and no reverse thrust–have to add those factors as well. Keep that number in mind to recheck before descent: if we’ve burned more fuel than planned, the margin gets better. If we’ve saved fuel by favorable winds or routing, the figures are wrong. Plus, we really won’t know for sure if the runway is dry, wet or icy until we’re much closer in.

Aircraft manufacturers, in compliance with FAA standards, have computed the Landing Distance chart very conservatively: they figured only about 75% of the actual brake effectiveness; they normal include zero reverse thrust.

Boeing jets have excellent autobrakes which can smoothly and easily apply Max braking, and do it evenly: if you’re landing with a lot of rudder input, you’ll have one leg extended and one bent back–try applying both pedals equally then. And antiskid computers apply the braking evenly on both gear until sensing an incipient skid, keeping the pressure just below that point, something humans can’t really perceive.

So, on landing, know before the wheels come down on final what the maximum weight for conservatively landing on a runway is, plus the adjustments to make in your head for the variables of winds and runway surface conditions. It’s best to have as wide a margin between our weight and the max, the most realistic, with conservative additives, estimate of what the jet and the runway can handle.

Takeoff is a similar max calculation, with a twist: what’s the maximum speed to which you can accelerate and still stop in the remaining runway? Same wild cards, curveballs and technical factors in play: winds, runway surface, equipment failures–including those that help us go (engines, high lift devices, flight controls) and those that help us stop (hydraulics, engines, reverse, tires, brakes, antiskid, electrical power).

Again, it’s coming at you fast on take-off roll because you’re accelerating and using maximum power for the adverse conditions. In the split second of a go or abort decision, you’d better discern if what you’re aborting for will compromise your ability to stop (see parenthesis in the above sentence) or eliminate your ability to fly–and you’d better be right.

LaGuardia, just prior to brake release.

Prior to applying takeoff power, review for myself the abort procedures that you must correctly do in the proper sequence (throttles idle, speed brakes, reverse thrust, brakes) and the dividing line: after 70 knots (considered the high speed-low speed dividing line), we’ll abort only for the mandatory items, which you also have memorized.

So we don’t even release the brakes till we have the big numbers pow-wow: planned weight, actual weight; takeoff power setting, N1 engine reading, V1 speed. You have to see it on the paper copy, on the glass (the FMS control head), on the flight management display (same numbers) and the Primary Flight Display, which is also repeated in the Heads Up Display projected on the glass in front of your face.

Now we’re ready to go–or, stop, as the case may be. Clear your mind of everything but the important stuff, know where you are in relation to each factor as speed increases and runway decreases, and be prepared to recognize developing situations and the proper options to handle them.

And that’s the long and short of jets and runways. Let’s go fly.

No comments:

Post a Comment